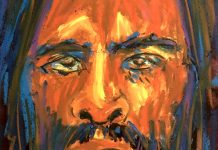

The centurion is a man of faith. He is able to trust, and trust blindly. He hasn’t even met Jesus, but he trusts that this new figure, this new healer and preacher, can help his beloved servant. And he trusts in his own actions, that they will get results, even though he describes himself as not worthy. None of us are ever worthy when we set out to act on behalf of others, but the essence of faith is to act and trust without needing to rely on a sense of our own perfection, or even of our own readiness.

It’s no accident that Luke brings John the Baptist back into the story at this point. John’s whole mission was to preach repentance from sin, and to baptize those who repented. The Greek word for sin that’s used in the Gospels is hamartia, which was used in the theater to describe a hero’s tragic flaw. It could also be literally translated as “missing the mark.” By using this word, the writers of the New Testament were saying two things: all of us have tragic flaws and are, like the centurion, unworthy; and, because of that flaw, when we try to do good, we will miss the mark (as Paul put it, “I find it to be a truth that when I try to do good, evil lies close behind). John offered baptism to people who had missed the mark and become aware of their own inherent flaws. But his baptism was one of repentance, which meant that those he baptized weren’t supposed to sit in a zero gravity, antiseptic state of inaction. They were supposed to take aim and try again.

John reveals the basic spiritual action – try, fail, repent, and try again. Jesus reveals the content of our attempts, the things that we should be trying for. “Go and tell John what you have seen and heard,” he says to John’s disciples. “The blind receive their sight, the lame walk, the lepers are cleansed, the deaf hear, the dead are raised, the poor have good news brought to them.” These are the things we should be attempting: seeing the world as it really is; trying to heal the world; returning people to our communities; hearing the truth in compassion and love; continuing along the path of our own deaths and resurrections; and being in active relationship with poor people.

We can’t do it without repentance. To add another Greek word into the mix, repentance is our translation of metanoia, which means “be of a higher mind.” To repent, we must move beyond our small, personal concerns, hopes, and worries, and try to see the entire world through the eyes of God. The Gospels assert that God cares for every hair on our heads, every flower of the field, every sparrow that flies and falls. If we were to look through God’s eyes, we would be as compassionately engaged with everything as God is, and we could treat nothing lightly (although we could, and should, treat it joyously).

Faith is the trust that we can do the things that Jesus tells us to, and even see through the eyes of God, even if we’re unworthy. It’s the hope that leads us to attempt an imitation of Jesus’s healing and teaching, because we see the fragility and beauty of everything. Such faith is, as Jesus points out, going to be derided and misunderstood. And we will fail many, many times as we try to live it out. But as we repent, and try again, our conversion will continue, and our tragic flaws, which may never leave us, will slowly be redeemed.